1 – MCS COMMITTEE

The AGM returned your committee to office, and at the subsequent first committee meeting, the following portfolios were allocated:

Chairman Gavin Stephens

Vice-Chairman Neil Rix

Treasurer TBA

Secretary Gaynor Lightfoot

Membership Jean Whiley

Committee Members Verity Bowman, Moira Fitzpatrick, Dennis Chitewe and John Dold

2 – NEW PARKS DIRECTOR ANNOUNCED

Professor Edson Gandiwa , a renowned wildlife ecologist and professor at Chinhoyi University of Technology, has been appointed as the new Director General of the Zimbabwe Parks & Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks).

Gandiwa, who previously served as ZimParks’ Director of Research, succeeds his former superior, Dr. Fulton Mangwanya, who recently assumed the position of Director General of the Central Intelligence Organization (CIO).

Dr. Gandiwa, married to fellow ecologist and Professor Patience Gandiwa, brings extensive experience to the role. Both have dedicated their careers to wildlife conservation within ZimParks under the leadership of Dr. Mangwanya.

Professor Gandiwa earned his PhD in Wildlife Conservation and Management from Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands. He has co-authored over 140 peer-reviewed scientific publications and has a distinguished research record in wildlife conservation, ecology, and environmental science.

He previously served as the Executive Dean of the School of Wildlife, Ecology, and Conservation at Chinhoyi University of Technology.

3 – CHINESE ARRESTED FOR POSSESING RHINO HORNS

NewsDay, Tuesday 25 February 2025

A 62-year-old Chinese national was dragged before the Harare Magistrates’ Court facing an allegation of possessing rhino horns valued at US$360,000 yesterday. Harare magistrate Sheunesu Matova remanded Lin Wang in custody to March 11 for routine remand after advising him to approach the High Court for bail application. Prosecutor Rufaro Chonzi alleged that on September 12 last year, Lin wanted to export a purported sculpture from Zimbabwe to China through Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport by Emirates Airways. The court heard that Lin met agent Cuthbert Maoko at the airport near the departure car park and went to National Handling Services (NHS) cargo handling area. While at NHS, Lin allegedly handed over a 13-kilogramme owl hardened-plastic sculpture to the agent to facilitate shipment to China.

4 – NEXT EVENT

Date | Sunday 16th March 2025 |

Venue | Diana’s Pool |

Meet | 08:00am, Ascot Car Park |

Travel | All vehicles but trucks preferred |

Please note that an entry fee is payable, $2 per person and $4 per car

Bring your picnic lunch, hat and, for the brave, swimming costume.

Following the recent good rains we are travelling out to Diana’s Pool to enjoy the site of rushing water and spilling pools. We will also walk to the Orbicular Granite Site. We are not certain of the road conditions after the recent rains but understand that they are passable via Mawabeni.

5 – REPORT BACK – ROWALLAN PARK

Our Annual General Meeting was held on 17th November at Rowallan Park – kindly hosted by Neil and Fiona Rix. The large veranda was a useful provision given the rain that was around that week-end.

Folk attending the AGM were able to visit Rowallan Adventure Camp and partake of a short walk before the main business commenced. The formalities were followed by an interesting talk by Dr Woody Cotterill on the recent geological conference held in Bulawayo, which included updates on the Matobo area. It seems that the orbicular granite remains an area of particular fascination, and we should probably be making more of this unique geological phenomenon than we hitherto do.

6 – AS FORESTS FELLED WOOD SHORTAGE HITS VILLAGERS IN ZIMBABWE

With acknowledgment to The Guardian, 13 November 2024. By Jeffrey Moyo, Chimanimani

Cart laden with firewood in Gonzoma, Zimbabwe, a picture that could just as easily have been taken in any of the Matopos Communal Lands.

Linet Makwera (28) has a baby strapped on her back as she totters barefoot, picking tiny pieces of wood on both sides of a dusty and narrow road, peering fearfully at people passing by along the road in Chimanimani’s Mutambara area in Gonzoma village located in Zimbabwe’s Manicaland Province, east of the country.

Her fears, Makwera says, are the patrolling plain clothes police officers, who often target people, cutting down the few available trees in search of firewood.

In the midst of firewood shortages countrywide, more than 300,000 trees were destroyed between 2000 and 2010, according to Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change.

In fact, in 2011, the Forestry Commission of Zimbabwe found out that the country was losing about 330,000 hectares of forests per year. According to Global Forest Watch in 2010, Zimbabwe had 1.01 Mha of natural forest, extending over 2.7 percent of its land area. In 2023, it lost 4.67 kha of natural forest, equivalent to 3.27 Mt of CO₂ emissions.

A slight drop from the previous one, currently, Zimbabwe’s annual deforestation rate is estimated to be at 262,348.98 hectares per annum, the Forestry Commission says.

According to UNDP in 2022, the use of local forests for fuel wood has also been one of the many drivers of deforestation in the country.

UNDP has been on record, saying presently, fuel wood accounts for over 60 percent of the total energy supply in the country and almost 98 percent of rural people rely on fuel wood for cooking and heating.

The Forestry Commission says up to 11 million tons of firewood are needed for domestic cooking, heating and tobacco curing every year in Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe is ranked top of the United Nations-ranked Least Developed Countries (LDCs) that have battled the highest rate of deforestation in the world, as many rural dwellers here depend on firewood for cooking.

Yet still, even as the felling of trees for firewood gets worse and worse in Zimbabwe, it is a crime for anybody to be found cutting trees for any purpose without the authorities’ blessing.

If caught on the wrong side of the law, a wood poacher can be fined $200 to $5,000

Like many villagers domiciled in her remote area, Makwera has to battle with firewood deficits as the forests disappear under massive deforestation.

But the laws prohibiting people from cutting down trees have also meant hard times for many, like Makwera.

Yet despite her struggles to find firewood often in order to cook food for her family, she (Makwera) has had to soldier on, just like many other villagers in her area.

With even the hills and mountains now running out of firewood in Makwera’s village, life has never been the same for the villagers, as they do not have electricity, which, even though it might have been there, would not have saved any purpose amid daily power cuts gripping the Southern African nation.

“Finding firewood is now a huge challenge. Yes, we buy. We have no choice. We suffer to find the firewood. In the hills and mountains where we used to find firewood, there is now nothing,” said Makwera.

Named using vernacular Shona, a tsotso stove typically is a tin with holes pricked into it, with a few tiny sticks stashed inside the home-made stove to produce some fire heat needed for cooking.

Stung by the growing firewood deficits, Zimbabwean villagers are even resorting to buying firewood from wood poachers moving around in scotch carts touting for customers.

Such are many, like 33-year-old Tigere Mhike, also a resident of Gonzoma village, who said he has been for a long time earning his living through selling firewood to the desperate villagers.

He does this illegally, and in order to escape the wrath of law enforcers, Mhike said he and his assistant often operate under the cover of darkness in their search for the wooden gold.

“Where we live here, there are now too many people who are crowded. Some pieces of land that had plenty of firewood are now occupied by more and more people. We now have to travel very long distances, waking up very early in the mornings sometimes at 2am to go and search for firewood so that we deliver to the villagers wanting the firewood. We sell one scotch-cart full of firewood at 25 (US) dollars,” said Mhike.

Amid incessant droughts actuated by climate change that have also led to the gradual disappearance of Zimbabwe’s forests, with the use of tsotso stoves requiring fewer wood sticks to produce the cooking heat, villagers here have said they are gradually adapting to the crisis.

Even to environmental experts like Batanai Mutasa, part of the panacea to surmount firewood deficits has turned out to be the now popular tsotso stoves in the face of Zimbabwe’s laws forbidding the cutting down of trees.

Mutasa is also the spokesman for the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA), a non-governmental organization comprising of legal minds fighting for this country’s environment.

As the trees disappear amid firewood poaching in Zimbabwe’s villages like Gonzoma in Manicaland Province, Mutasa has a piece of advice.

“My advice to people struggling to find firewood in remote areas is that they should work together to find other means that protect our trees from being damaged, things like using biogas or stoves that don’t require much firewood like tsotso stoves,” he said.

In worst case scenarios, said Mutasa, to preserve forests as they search for firewood, people should resort to just plucking off branches from the surviving trees to use these to make fire, leaving the trees alive.

Mutasa said: “Mainly, people should make it their habit to plant and replant trees. People can team up with authorities in their villages to fight off wood poachers in their areas.”

Another Gonzoma villager, Mzilikazi Rusawo, in his early sixties, said faced with desperate times in their search for firewood as the few forests are jealously guarded by law enforcers, they now have to seek permission from authorities before they cut selected trees for firewood.

“The law does not allow us to just cut down trees for firewood anyhow. We actually seek permission from authorities before cutting trees for firewood, which we do with care—sparsely cutting down the trees in order to leave many other trees standing,” said Rusawo.

For the Zimbabwean government, the options are, however, fast running out as rural dwellers battle with firewood shortages.

Some of the options cannot be afforded by many residents in rural areas in a country where more than 90 percent are jobless, according to the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU).

“Firewood shortages are a huge challenge for all people living in rural areas, but it is not only firewood that can be used for cooking. People can also use biogas,” said Joyce Chapungu, spokesperson for the Environmental Management Agency (EMA).

With the retail price of biogas in Zimbabwe going for approximately two dollars per kilogram, not many rural residents can afford buying the cooking gas.

7 – UNESCO AND BIRDLIFE ZIMBABWE PARTNER TO RAISE AWARENESS OF WETLANDS CONSERVATION

With acknowledgment to UNESCO, 8 November 2024

Since the 1700s, nearly 90% of the world’s wetlands have degraded, with their loss occurring at a rate three times faster than that of forests. Urban wetlands are highly vulnerable. This highlights the urgent need for collective efforts to address and reverse the decline of these critical ecosystems.

Wetlands in Harare, including Ramsar Sites, face threats from drainage, conversion to development, cultivation and pollution. These activities have caused increased siltation in Harava and Seke Dams, as well as Lakes Chivero and Manyame, leading to water shortages, eutrophication from excess nutrients, and a loss of biodiversity essential for ecosystem health and human well-being. To address these challenges, BirdLife Zimbabwe, in collaboration with UNESCO ROSA and Harare Wetlands Trust, and with funding from the Netherlands, is hosting a series of workshops to identify the most effective strategies for protecting wetlands. The outcomes of these workshops will be presented at the Ramsar Convention in 2025.

The first workshop, held at Lake Chivero, brought together participants who shared the status of Harare’s wetlands, which have been worsening over time and developed an action plan with recommendations to enhance the protection and restoration of these ecosystems. The strategies and recommendations included the establishment of a National Committee, comprising all relevant stakeholders, to address wetlands issues. Additionally, the need for strong awareness-raising campaigns on the importance of wetlands was emphasized, among others.

As growth and development continue, the demand for water is increasing. However, water supplies are steadily diminishing due to the degradation and loss of natural wetland infrastructure, depletion of groundwater resources, and the growing impacts of climate change. Amidst this development, it is essential to preserve and protect our wetlands, as their destruction undermines nature’s own system for providing sustainable freshwater to the area.

The terrible water situation in Harare is directly related to wetlands loss, as Zimbabwe’s capital relies on headwater wetlands for water supplies. The city is unable to provide adequate supplies of clean water which negatively impacts marginalised and poor communities.

If current trends continue, Harare’s surviving wetlands may be completely destroyed over the next several decades. Without wetlands, the city will experience more frequent water shortages, increased flooding, and poor water quality. The environmental and societal consequences of this loss might be devastating for Zimbabwe’s capital.

UNESCO ROSA Programme Specialist, Guy Broucke encouraged participants to start empowering themselves with knowledge about the wetlands, understanding the current threats they face, appreciating their significance, and recognizing why their involvement matters.

The workshop was attended by the Ministry of Local Government, The City of Harare, Environmental Management Agency, Upper Manyame Sub-Catchment Council, ZimParks Conservation Society of Monavale, Emerald climate hub, African Youth Initiative on Climate Change Zimbabwe and Zimbabwe Youth Biodiversity Network.

Zimbabwe will be hosting the COP 15 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands at Elephant Hills, Victoria Falls from 23-31 July 2025. Every small action count, and together we can ensure the long-term health and sustainability of our wetlands.

8 – THIRSTY, ENERGY-HUNGRY STEEL ‘MONSTER’ SET TO DESTROY THOUSANDS OF LIMPOPO PROTECTED TREES IN INDUSTRIAL DRIVE.

With acknowledgment to Tony Carnie, 14 November 2024

Opponents of the heavy industry plan fear the development will cause irreversible environmental harm to a large section of the Vhembe biosphere reserve. (Photo: Gallo Images / GO! / James Gifford)

Tens of thousands of indigenous trees, including baobabs and other specially protected species, are set to be the first casualties of a massive heavy industry development plan in Limpopo. The scheme is driven by the provincial government and Chinese developers, who have touted it as ‘the most competitive energy metallurgy special zone in the world’

Permit applications sent to the national Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment (DFFE) show that there are plans to destroy as many as half a million protected indigenous trees in the 12,000-hectare Musina-Makahado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ) in northern Limpopo. This appears to exclude the further destruction of tens of thousands of other more abundant indigenous trees such as mopanes, bushwillows and clusterleafs.

So far, the department confirmed that it has issued licences for the destruction of 1,000 specially protected trees but forestry officials said they would adopt a “cautious and responsible approach” when considering another application to destroy a further 9,000 protected trees.

But there is also a more alarming application in the wings: to remove or destroy more than 650,000 protected trees that include 10,000 baobabs, 100,000 shepherd’s trees, 120,000 marulas and 428,058 leadwood trees.

Apart from the significant scale of biodiversity damage from tree felling, the plan to develop a new heavy industry zone in Limpopo has also raised concern about whether there is enough water and electricity available in the region to support a mega-scale scale development centred around steel smelting, coal washing and other metallurgical processes.

Botanists voted to change the name of hundreds of plants to remove a racial slur in their scientific names. They also voted to allow a committee to evaluate new species names that could be offensive or derogatory, starting in 2026.

Nevertheless, the project has received official backing from President Cyril Ramaphosa, Limpopo provincial Premier Phophi Ramathuba and several China-based steel, coal and metallurgy companies. The investors have been wooed with a range of government incentives that include corporate income tax of 15% instead of 27%, as well as cheap electricity supplies, potentially from the Medupi Power Station.

9 – IN A FIRST, BOTANISTS VOTE TO REMOVE OFFENSIVE PLANT NAMES FROM HUNDREDS OF SPECIES.

An international body has voted to make the change and to further consider the ethics of scientific names. With acknowledgement to Rodrigo Perez Ortega and Erik Stokstad.

The scientific name of the gifbossie, a flowering plant from South Africa, will change from Gnidia caffra to Gnidia affra. Bob Gibbons/FLPA/Minden Pictures

Alina Freire-Fierro, a botanist at the Technical University of Cotopaxi who was not involved with proposing the changes, says she’s glad that culturally offensive names were discussed at the International Botanical Congress in Madrid, where the vote was held. “It was about time,” she says.

This is the first time that botanists have voted on changing names that could be offensive. Their decision will eliminate a “c” in more than 300 scientific names of plants, algae, and fungi that include caf[e]r- and caff[e]r-. The one-letter change would mean removing references to caffra, an Apartheid-era slur used to discriminate against Black people in South Africa, in favor of affra and related derivatives, implying simply that the species has its origins in Africa.

“[We] express our gratitude to our colleagues from around the globe who supported our efforts to rid botanical nomenclature of a despicable, racial slur,” says Gideon Smith, a plant taxonomist at Nelson Mandela University who initiated the renaming proposal.

In a secret ballot among 556 botanists physically at the Madrid meeting, 63% voted to accept the change. But discussions leading up to the vote have been heated for years. Debates over scientific names have erupted among botanists since at least since 2021. Some have pushed to restore Indigenous species names and change offensive ones, such as those in the genus Hibbertia, which was named in honour of English anti-abolitionist and plantation owner George Hibbert. A few botanists have also proposed getting rid of eponyms honouring humans altogether, arguing that they’re “out of step with equality and representation.” Other researchers have pushed back, saying scientific nomenclature shouldn’t be swayed by social movements.

Natural History Museum of London botanist Sandra Knapp expressed concern about the bickering factions last year in an interview with Science. “What I find really sad about this is that there’s a lot of vitriol, there’s a lot of unpleasantness associated with this, which I kind of feel there doesn’t need to be,” said Knapp, who also serves as president of the nomenclature section that voted on the changes today.

Taxonomists are often reluctant to alter species names, because these changes can cause confusion and must be revised in databases and sometimes in legislation, such as protections for endangered species. The proposals accepted today by botanists’ contrast with what the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature decided last year. That group arbitrates on the correct use of scientific names of animals and announced it will not consider changing animal names many researchers consider offensive.

“Even small changes [in names] could have ripples, unforeseen circumstances that cause costs and difficulty for everyone,” says Quentin Groom of the Meise Botanic Garden, who attended the botany session today in Madrid. “So, there are conflicting pressures. And you definitely felt that in the room.”

Today’s vote among botanists also included a proposal to more broadly allow existing culturally offensive names to be changed and to set up a new permanent committee to rule on these decisions going forward. But that original proposal was amended before it was voted on and passed. Instead of a new group, an existing committee that evaluates names that may be invalid for other reasons, such as prior discovery, will also handle requests to change names deemed offensive. This committee will only consider objections to new plant scientific names that have been published after 1 January 2026 and not retroactively correct names. This way, the scientific community “can deal with new names, but obviously that’s much less of a problem” than older names, Groom says.

Botanists will continue to contend with existing offensive names and other ethical issues in taxonomy. An ad hoc group will consider such names and report back at the next Congress in 6 years. “The community does want to do something, but you’re talking about a very cautious bunch,” Groom says.

10 – RELENTLESS POACHERS BUTCHER 20 DEHORNED RHINOS IN KZN SANCTUARY

With acknowledgement to Tony Carnie, 13 November 2024

WWF rhino range expansion coordinator Ursina Rusch and Ezemvelo conservation staff Hloniphani Qwabe and Musa Nkosi (right) collect blood samples prior to the dehorning of another rhino in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Game Reserve. (Photo: Vanessa Duthe)

The dehorning project in the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi rhino sanctuary in KwaZulu-Natal has suffered a setback, with at least 20 dehorned animals gunned down for their remnant horn stumps over the past month. Earlier this year, a massive operation began in the 96,000ha Hluhluwe-iMfolozi rhino sanctuary to remove the horns of hundreds of rhinos to reduce the relentless poaching in a state-owned park that still protects a significant portion of the beleaguered species.

The Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife management agency had previously resisted calls to dehorn rhinos in the park — partly due to the significant expenses, and because the sanctuary was one of the few major parks where tourists could still see rhinos in their natural state. However, following an offer of financial and other assistance from the WWF South Africa conservation group, Ezemvelo embarked on a joint operation in April to dehorn more than 1,000 rhinos. The operation, with further assistance from Wildlife ACT, Save the Rhino International and Zululand Wildlife Vets, led to immediate conservation dividends. According to WWF, the mass dehorning resulted in a sharp 70% to 80% drop in poaching in the park. However, now it has emerged that at least 20 dehorned rhinos were killed in October by a poaching gang believed to be connected to a Mozambique-based syndicate. While the aim of dehorning is to remove as much of the horn as possible (to make it less attractive to kill animals with no visible horns) conservation staff leave behind a small portion to prevent injury or permanent damage to the growth plate at the base of the horns. In a media statement recording a recent visit to the park by Zulu King Misuzulu, Ezemvelo said that despite initial success, “October saw an unfortunate spike, with 20 dehorned rhinos lost to poaching. “However, Ezemvelo hopes that it has dismantled the syndicate following the death of two foreign poachers shot during the gun battle between them and Ezemvelo’s anti-poaching unit. “Commenting on the recent killings of the dehorned rhinos, WWF rhino conservation programme manager Jeff Cooke said it was still too early to declare that the project was not working. Cooke — who spent 34 years of his career at Ezemvelo, including heading the game capture and veterinary services unit — said he would prefer to wait until the end of the year to review the statistics over a longer time frame. “This is not a simplistic success/failure issue. The fact is that the poaching rate has declined significantly since the project started in April. We have had several good months and one bad month, and we also have to ask how many more rhinos would have been poached if we had done nothing. “Nevertheless, said Cooke: “This is a wake-up call for Ezemvelo and other conservation agencies that you cannot just dehorn rhinos and then take your foot off the pedal. “These guys are in it for the money, so if they think they can get away with poaching the stumps from dehorned animals — without getting arrested — then it’s still worth their effort, although we know that local syndicates are generally looking for the whole horn intact. “As a result, it was vital for conservation staff to remain on high alert and to ensure that staff had the necessary capacity and intelligence support to intercept poachers, preferably before they entered parks. Ezemvelo has installed a large number of surveillance cameras in the park that trigger immediate responses from ground teams, erected strategically placed “smart fencing” to monitor specific areas of the park and uses K9 units to track poachers in the park.

11 – THAT BITE OF SUMMER HAS WELL AND TRULY COME EARLY THIS YEAR AND WITH THAT HEAT COMES SNAKES.

With acknowledgement to Rob Timmings and edited for Zimbabwe conditions.

In Australia, 3000 bites are reported annually, which result in 300-500 hospitalisations and 2-3 deaths.

Average time to death is 12 hours. The urban myth that you are bitten in the yard and die before you can walk from your chook pen back to the house is a load of rubbish.

While not new, the management of snake bite (like a flood/fire evacuation plan or CPR) should be refreshed each season.

Let’s start with a basic overview.

In Zimbabwe poisonous snakes belong to four families: Colubrids (Boomslang), Vipers (Puff Adder), Elapids (Mambas and Cobras) and Atractaspids (Bibron Stilleto snake). The Puff Adder is responsible for three quarters of the bites.

All snake venom is made up of huge proteins (like egg white). When bitten, a snake injects some venom into the meat of your limb (NOT into your blood).

This venom cannot be absorbed into the blood stream from the bite site.

It travels in a fluid transport system in your body called the lymphatic system (not the blood stream). Now this fluid (lymph) is moved differently to blood.

Your heart pumps blood around, so even when you are lying dead still, your blood still circulates around the body. Lymph fluid is different. It moves around with physical muscle movement like bending your arm, bending knees, wriggling fingers and toes, walking/exercise etc.

Now here is the thing. Lymph fluid becomes blood after these lymph vessels converge to form one of two large vessels (lymphatic trunks) which are connected to veins at the base of the neck.

Back to the snake bite site.

When bitten, the venom has been injected into this lymph fluid (which makes up the bulk of the water in your tissues).

The only way that the venom can get into your blood stream is to be moved from the bite site in the lymphatic vessels. The only way to do this is to physically move the limbs that were bitten.

Stay still!!! Venom can’t move if the victim doesn’t move. Stay still!!

Remember people are not bitten into their blood stream.

In the 1980s a technique called Pressure immobilisation bandaging was developed to further retard venom movement. It completely stops venom / lymph transport toward the blood stream.

A firm roll bandage is applied directly over the bite site (don’t wash the area).

Technique:

Three steps: keep them still

- Step 1 Apply a bandage over the bite site, to an area about 10cm above and below the bite.

- Step 2 Then using another elastic roller bandage, apply a firm wrap from Fingers/toes all the way to the armpit/groin. The bandage needs to be firm, but not so tight that it causes fingers or toes to turn purple or white. About the tension of a sprain bandage.

- Step 3 Splint the limb so the patient can’t walk or bend the limb.

Do nots:

- Do not cut, incise or suck the venom.

- Do not EVER use a tourniquet

- Don’t remove the shirt or pants – just bandage over the top of clothing.

- Remember movement (like wriggling out of a shirt or pants) causes venom movement.

- DO NOT try to catch, kill or identify the snake!!! This is important.

In hospital we NO LONGER NEED to know the type of snake; it doesn’t change treatment.

Five years ago, we would do a test on the bite, blood or urine to identify the snake so the correct anti venom can be used.

BUT NOW…

we don’t do this. Our new Antivenom neutralises the venoms of all the 5 listed snake genus, so it doesn’t matter what snake bit the patient. (in AUSTRALIA not Zimbabwe)

Read that again- one injection for all snakes!

Polyvalent is our one-shot wonder, stocked in all hospitals, so most hospitals no longer stock specific Antivenins.

Allergy to snakes is rarer than winning lotto twice.

Final tips: not all bitten people are envenomated and only those starting to show symptoms above are given antivenom.

12 – DROUGHT IMPERILS ZIMBABWE’S ANCIENT ROCK ART, SPURRING EFFORTS TO PRESERVE AND DATE IT

With acknowledgement to Diana Kruzman, 27 Nov 2024

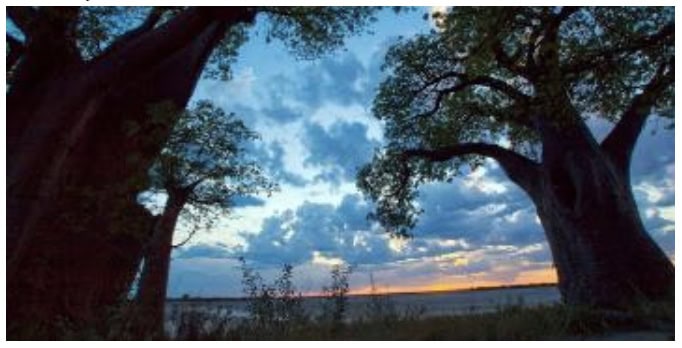

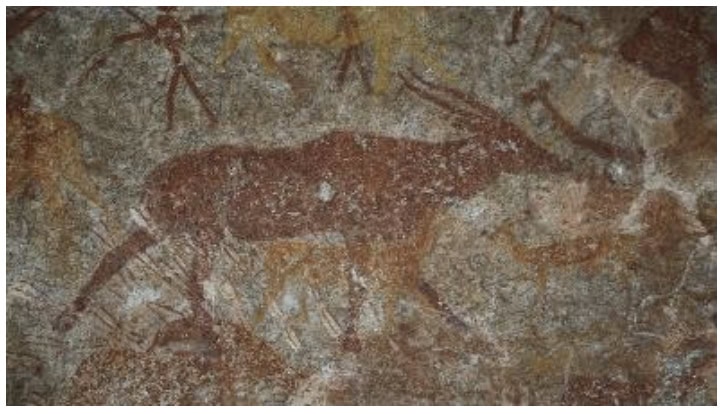

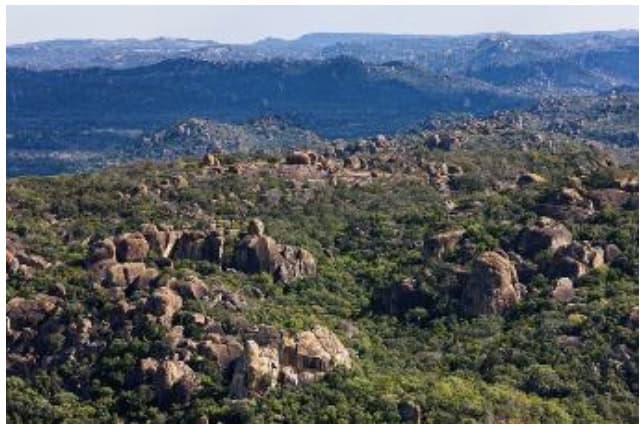

THE MATOBO HILLS IN ZIMBABWE—Sketched onto the walls of a granite outcropping in the hills of southern Zimbabwe, tall, rust-red human figures gather around groups of antelopes and giraffes. The painting, along with more than 3000 others in the area, portrays animals spiritually important to the nomadic San people who created them sometime between 2000 and 13,000 years ago. This pictorial record of San culture in the Matobo Hills is one of Africa’s highest concentrations of rock art; it was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003.

Ancient rock art made by the San people depicts an eland and human figures. Steve O. Taylor.

But the paintings are under threat from vandalism as well as erosion. Now, a nonprofit group near the hills is working with local people to document and raise awareness of the rock art before it disappears. Since July, the Amagugu International Heritage Centre (AIHC), based in the village of Whitewater near the southern city of Bulawayo, has been collaborating with the U.S. embassy in Zimbabwe and the country’s national museum to record local stories about the art, identify new sites, and develop a catalogue of artworks that can be analyzed by experts even if the original paintings fade. The team plans to release a final catalogue and a documentary about the project in January 2025.

Preserving the art is essential to understanding the ancient societies that created it, said Ancila Nhamo, a professor of archaeology at the University of Zimbabwe working on the project. “Art is a product of the mind and the culture, which is an intangible thing,” she said. “But when you get the art, you can get into the minds of these people and really see what the world was like at that time.”

This year, Zimbabwe has undergone one of the worst droughts in living memory, with maximum temperatures 2°C to 5°C above normal. Hot, dry weather boosts the risk of wildfires and kills vegetation, increasing soil erosion and making rock art sites more prone to flooding during the rainy season, as researchers in nearby Namibia have found.

The paintings are also vulnerable to vandalism, such as graffiti, and damage from fires, which are sometimes set by locals unaware of the paintings’ importance. Unlike previous efforts led by outsiders, this project aims to inspire a sense of ownership over and responsibility for the sites among local people. “The [local residents] are the people who should play a part in preserving, documenting, and protecting this cultural heritage,” said Allington Ndlovu, a program manager at AIHC.

The people in the area today are mostly farmers of the Ndebele ethnic group, whose ancestors migrated from the north in several waves starting about 4000 years ago. The ancient Ndebele interacted with the nomadic San, whose descendants still live in some parts of Zimbabwe and in South Africa. Today, San people feel the rock art can help them understand their heritage, said Davy Ndlovu, director of the Tsoro-o-tso San Development Trust, a Zimbabwean nongovernment organization that advocates for the rights of the Indigenous group. “The cultural heritage of the San is critically endangered and there is very little awareness around the issue,” Ndlovu said. “Projects like this can assist the San to get their voices heard … and assist coming generations to understand the heritage of Zimbabwe.”

The project organizers worked with local leaders to train 35 women from seven villages in drawing and painting techniques. The local artists then replicated 35 artworks using pencils, brushes, and paint, creating a visual record now displayed in a community gallery. Fourteen of the largest and clearest rock paintings were reproduced on canvas and granite slates, to be displayed in the country’s national gallery.

Meanwhile, a joint French-Zimbabwean research project called MATOBART is working to date rock art in the Matobo Hills. The paint is made of inorganic material so it can’t be radiocarbon dated, said project leader Camille Bourdier of the University of Toulouse-Jean Jaurès. Instead, she and other researchers set out to date stone tools, including palettes likely used to create the paintings, and flakes of paint that fell to the ground. They hope to estimate minimum ages by directly dating the sediment around these artifacts.

Preliminary findings confirm earlier estimates made by archaeologists in the 1980s, who suggested the paintings were created starting about 13,000 years ago. More precise dating will allow researchers to more accurately interpret the art, Nhamo said. For instance, rock art in Zimbabwe mainly depicts kudu antelopes, she says, whereas similar San sites in nearby South Africa focus on another antelope, the eland. Nhamo would like to know whether San people painted different animals over time, or distinct San groups valued particular animals as markers of community identity, a way to distinguish themselves from their neighbours.

Other interpretations focus on the spiritual, rather than social, importance of the animals, said Sam Challis, who heads the Rock Art Research Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand. San people started to paint “richly embellished” eland at sites in the Drakensberg Mountains during a period of cooler climate that began around 1500 B.C.E., when the animals—previously a staple food source—were becoming more scarce, as Challis and anthropologist Brian Stewart of the University of Michigan wrote in a 2023 paper. They argue that by painting the eland, the San were attempting to harness the antelope’s spiritual powers to summon more of them to appear during a time of scarcity.

The artworks now being documented in the Matobo Hills, including scenes of antelopes, elephants, and gnus surrounded by humans walking with bows and arrows and dancing or sitting, could yield similar insights for future researchers, Bourdier said. “These [San] hunter-gatherers have been living this way for tens of thousands of years. … It has proven to be a very sustainable way of living,” she said. “Unravelling these ways of living within the world could give us some clues of the type of behaviours or relationships we could go back to.”

13– RAINFALL

The first rains fell in late October – isolated and light, and the brief wet spells were interspersed with long and very hot periods, right through December. Another year of drought loomed on the horizon.

Finally meaningful rain started to fall towards the end of December – probably too late to improve crop fields in the rural areas, but hopefully will continue so as to refill the wetlands, streams, rivers and dams and so secure water for the year ahead. At this stage it seems we are going to receive above average, and through the month of February the dams within the Park all filled and started to spill, whilst the Matopos Dam took in a fair bit of water. The Hills are alive once more!

Rainfall measures at 24 February – Eastern Hills 784mm, Central Hills 668mm, Western Hills 696mm

14 – COUNCIL PUMPS RAW SEWAGE INTO LAKE CHIVERO AND KILLS FOUR RHINO – HARARE CITY

With acknowledgement to The Herald

Council has been discharging raw sewage into the Mukuvisi River, which flows into Lake Chivero, the city’s main water source, for the past two weeks. This has created serious health and environmental hazards, resulting in Zimparks banning all fishing activities at Lake Chivero, where thousands of fish have died, alongside animals including four rhinos and three zebras. The pollution, primarily from raw sewage, has caused a surge in cyanobacteria, posing health risks to both humans and wildlife.

15 – SOCIETY CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR YOUR DIARY

26 – 30 March 2025 Matopos Heritage MTB Challenge

7 June 2025 Matopos Clean-Up Day for World Environment Day (5 June)

22 – 24 August 2025 Matopos Heritage Trail Run

22 September 2025 World Rhino Day

28 – 30 November 2025 Matobo Classic

16 – MEMBERS NOTEBOOK

Subscriptions

Subscriptions for the year 1 October 2024 to 30 September 2025 are now due. Please ensure that your subs are up to date. There has been no increase in rates.

US$ 20 Individual/Family

US$ 5 Pensioner/Student

US$100 Corporate

If you need any information, please contact matoboconservatiosociety@gmail.com

MCS Branded Apparel

The Society has a small stock of sleeveless fleece jackets, in olive green with orange MCS logo, available at US$20 each. They are ideal for the cool mornings and evenings. We also have stocks of hats and caps at $10 each. CD’s and shopping bags are also available at $5 each. Additional branded apparel (such as khaki shirts, fleece jackets, golf shirts) can be ordered on request. Please contact the Secretary via WhatsApp +263 71 240 2341 for further details

Website – www.matobo.org

Visit our website and make use of the RESOURCES tab for maps and information.

Don’t forget to join our Facebook page, with over 800 members now.

The Natural History of the Matobo Hills

This MCS publication is available at the Natural History Museum for US$20 (Reduced from $30)